They don’t advertise for killers in the newspaper. That was my profession. Ex-cop. Ex-blade runner. Ex-killer.– Rick Deckard

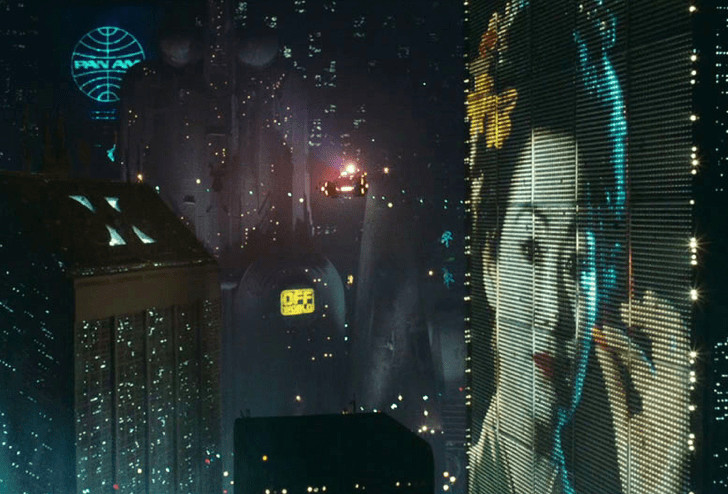

The year is 2019, and the city is Los Angeles. It’s a city of the future, bright lights, hover cars, holographic ads. It’s also a city of filth and crime and humanity. It’s the city where the stage is set for an epic of neo-noir sci-fi taken from the pages and mind of celebrated author Philip K. Dick, and brought to life on the big screen under the guiding hand of Ridley Scott.

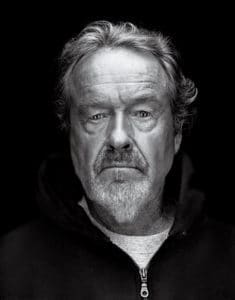

Both Philip K. Dick (pictured left) and Ridley Scott (pictured right) are legends in their respective fields. Dick was one of the great science fiction authors of the 20th century. His numerous books are counted as some of the finest examples of the genre, as well as his dysptopian fiction. One only has to look at other movies like Total Recall, Scanner Darkly, Minority Report and The Adjustment Bureau, to see that Hollywood and the movie industry are in love with his stories. And for Ridley Scott, well a listing of his achievements could go on for pages and pages. He is a master director, giving the world such films as Alien, Gladiator, Black Hawk Down, American Gangster and Prometheus. Ridley Scott is a credit to the film-making community, and his handling of taking Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? and turning it into Blade Runner is nothing short of amazing.

Every cast member of the film brings a complex character to the big screen. From Harrison Ford’s performance as the hard Rick Deckard, to Rutger Hauer’s manic role of Roy Batty, to Sean Young giving life to Rachael, each cast member adds a layer of depth to the story, no matter how large or small their role. This is why the world of Blade Runner is so fantastic, every person, human or replicant has a story to tell. Some of the stories are obvious and easy to see, some require the imagination of the audience to fill in the gaps. Either way, the principle players of this tale and the minor ones are all persons that viewers can latch onto.

Every cast member of the film brings a complex character to the big screen. From Harrison Ford’s performance as the hard Rick Deckard, to Rutger Hauer’s manic role of Roy Batty, to Sean Young giving life to Rachael, each cast member adds a layer of depth to the story, no matter how large or small their role. This is why the world of Blade Runner is so fantastic, every person, human or replicant has a story to tell. Some of the stories are obvious and easy to see, some require the imagination of the audience to fill in the gaps. Either way, the principle players of this tale and the minor ones are all persons that viewers can latch onto.

Thematically there’s a lot going on throughout the production. Largely using elements of film noir, there are also under-layers of literature, religion, drama, and philosophy. A major theme is that of human mastering of genetic engineering and its widespread implications upon the environment and society as a whole. Then there is the constant question of whether or not Deckard himself is a replicant (the scene involving a parting gift of an origami unicorn plays to the dream of Deckard and a unicorn running through a forest, indicates that if he is a replicant, his memory tapes were accessed by fellow policemen). What makes this movie so great is that there is a level of ambiguity at play with the themes, allowing audiences to form ideas about the story from varying perspectives.

Despite its failing at the box office’s in 1982, the movie has become a science fiction classic, praised by critics such as Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss. But there is also a bit of tragedy attached to the success of the movie, in the form of there being seven, that’s right seven versions of Blade Runner released over the years. From the Workprint that was shown to test audiences, to the Final Cut that was released in 2007, this is a tale of studio control over director control and it’s a sorry one indeed. Going back to the Workprint in 1982, there have been multiple changes to the story, scenes cut due to audiences not grasping the story, narrations added without Scott’s approval, and a studio-imposed ‘happy ending’ that altered the original direction of the plot. All these changes show what can happen when studio heads and money men take control, wrecking an artist’s vision in order to turn a profit.

Despite its failing at the box office’s in 1982, the movie has become a science fiction classic, praised by critics such as Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss. But there is also a bit of tragedy attached to the success of the movie, in the form of there being seven, that’s right seven versions of Blade Runner released over the years. From the Workprint that was shown to test audiences, to the Final Cut that was released in 2007, this is a tale of studio control over director control and it’s a sorry one indeed. Going back to the Workprint in 1982, there have been multiple changes to the story, scenes cut due to audiences not grasping the story, narrations added without Scott’s approval, and a studio-imposed ‘happy ending’ that altered the original direction of the plot. All these changes show what can happen when studio heads and money men take control, wrecking an artist’s vision in order to turn a profit.

A broadcast version for US audiences in 1986 had edits made to tone down the mature themes of the story, making it compliant with broadcasting restrictions. Seven years later in 1992, an official Director’s Cut was re-released to theaters after the negative backlash from Ridley Scott over screenings of the 1982 Workprint. Scott had a direct hand in the Director’s Cut, bringing his might as a storyteller to bear in the form of edits that brought things back to the way they were supposed to be in 1982. The cuts were as follows: all 13 of Deckard’s narrations removed, insertion of the dream sequence involving Deckard and a unicorn, as well as removal of the ‘happy ending’. It wasn’t until 2007 when the 25th Anniversary Edition (a 5-disc set containing the Workprint, both the US and international 1982 releases, the 2006-remastered director’s cut and the 2007 final cut which was restored from the original negative) that a “definitive” version (the final of Scott’s 1982 masterpiece) was finally presented to the viewing public.

Now with the sequel Blade Runner 2049 coming out this fall, film goers and fans of the original will get to thrill to Harrison Ford taking up the role of Deckard once more, pairing with Ryan Gosling for what is sure to be another noir science-fiction epic. While Ridley Scott may not be directing this new movie, he is still attached in a producer capacity, and will no doubt extend much of his same vision over the next (and perhaps final) chapter for the story of Rick Deckard.

Blade Runner is one of those movies that demands being watched over and over, even if the viewer has seen it a hundred times; its story, characters, dialogue, action and sets never grow old. Deckard’s hunting of the rogue replicants is something everyone can get behind, or if one wants to sway the other way, cheer for the replicants in their mission to gain more life and become more than the sum of their programming and artificial lives. Whether someone is a fan of sci-fi, noir or just loves Harrison Ford during his glory days as an actor, there is something for every person who sits down to watch or re-watch the film. Another top notch example of the level of master movies that were released during the 1980’s, combining some of the best parts of other popular genres into one complete and fantastic whole.